Lure Color Selection

* This page contains affiliate links. The Great Lakes Fisherman may earn a commission on items purchased through these links. For more on this, please click here.

Color selection for fishing lures is a controversial topic. Everyone has an opinion on what a fish wants and why. But what does science say about the matter? I think we can all agree that color matters, but how do we know which colors work best in any one scenario? Here we will explore light properties under the water and how that impacts lure color selection.

How Fish See Color

Before we go any further, it is important to note that a fish’s vision is very similar to that of humans. They have cells that process light in very similar ways to us both during the day and at night. This is important because as we understand how colors change in the water, we will understand how a fish sees it. One minor difference is that a fish’s visual range is a bit broader than ours, allowing them to detect some ultraviolet light that we can’t see. But this difference is, for practical purposes, irrelevant. So for our purposes here, we can assume that fish see things generally the same way as we do.

Light and Color

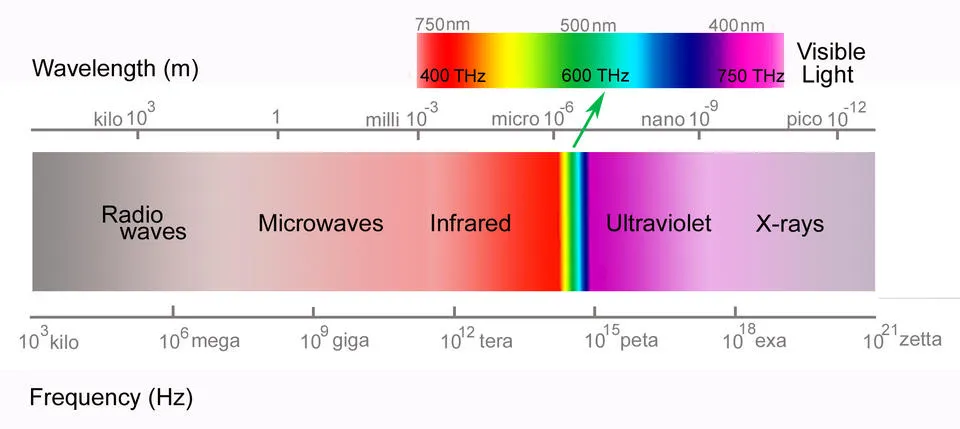

Although light is still not fully understood by science, many of its properties are. Color is one of them. Each light ray has a property known as frequency and wavelength. In a sense, these are one and the same as they are inverses of each other. The higher the wavelength, the lower the frequency and vice versa. Quite simply, each frequency/wavelength of a light ray that hits your eye is correlated to the color that you see.

When these rays hit the retina at the back of your eyeball, they enter a line of cells called cones. These cells come in three varieties to detect just 3 colors: red, green and blue. From there, signals are sent to your brain where your brain process all 3 signals and turns them into the color you “see”.

Light frequencies span a very large range. But there is only a small range of these frequencies that is known as visible light and this is the only light we can “see” with our naked eye. The visible range starts at what we see as red light on the lower frequency end and goes up to violet light at the higher frequency end. Light frequency that is below the red end of our visible range is known as infrared light (meaning “below red”). Frequency above the violet end of our visible range is known as ultraviolet light (meaning “above violet”).

Color Changes with Water Depth

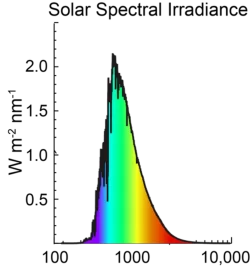

Nearly all light in the water column is coming from the surface. During the day, most of that light is coming from the sun which carries all frequencies of visible light. However, the sun doesn’t deliver these frequencies in equal amounts. The chart below indicates the relative intensity of the various light wavelengths emitted by the sun that are within the visible range.

From the chart, we can see the the green region of the spectrum has the most intensity. Put quite simply, there is more of this green light entering the water column than any other. This is important in understanding how things are seen under the water.

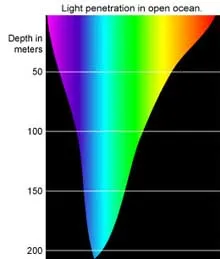

But this doesn’t tell the whole story. The higher the frequency, the more the light will penetrate the water column. This means that lower frequencies will be absorbed by the water more than higher frequencies. As a result, almost all of the red light will be absorbed in the top part of the water column. To the contrary, violet light will penetrate the deepest.

So if we combine the relative intensity of each frequency with the depth at which it can penetrate, we get something that looks like the following diagram.

From this diagram we can see that the combination of intensity and penetrability make bluish-green light the most abundant in deep water. So how can we use this information to help understand what a lure looks like under the water?

How Lures Reflect Light

Now that we understand how much light of various frequencies is in the water column, let’s discuss how that light interacts with the lures we put down there. To do this, we need to understand how light is reflected off of objects. This will tell us how light “looks” coming from the lures.

Every material absorbs and reflects light differently. When we perceive an object’s color, it is due to the combination of reflected light frequencies that are hitting our eyes.

For example, when we see the color red, that means that based on the combination of the light frequencies that are reflected off of the object, our brain is interpreting that as red. This might be because the only light frequency hitting our eye is red light. But usually it is because the combination of frequencies hitting our eye results in our brain processing them as red. Either way, we see the object as red.

Impacts on Lure Selection

So now that we understand how light interacts with the water and lures, how can we make use of this information to our advantage?

Suppose you are trolling for salmon in 100′ of water and are marking fish. As a result, you have your trolling spoons set 50′ down. Earlier in the spring, you were catching easy limits in shallow water (less than 20′ deep) on orange spoons and you decide to include a healthy number of those colors in your trolling spread. To your surprise, you are not catching anything on those colors. You have, however, been consistently getting bit on two green spoons that you have down there. What is going on? How could a color that was so hot in the spring be so cold now?

Referencing the chart above, we can see that red and orange light doesn’t penetrate very deep into the water column. This means that the orange lures will look significantly different in the deep water than what they looked like in the shallow water back in the spring. To be fair, any color will look different in deeper water, but the closer the lure colors are to the colors that penetrate that depth, the less change there will be in their appearance. This also doesn’t mean that fish won’t hit a red or orange lure in deep water. But it does mean that those lures won’t show up nearly as well as some of the colors in the middle of the spectrum, such as hues of blue and green.

Water Clarity Affect on Color

So now that we have discussed water depth, what about water clarity?

We all know what happens when we put on a pair of those yellow sunglasses. It doesn’t just change the intensity of the light, but it changes the colors we see as well. A similar thing happens in stained or turbid water. The suspended particles in the water absorb and reflect light just like any other material. Based on what is in the water, certain frequencies of light will be absorbed and others will be reflected. This causes a change to the perceived color of a lure in the water. This is why certain colors work better in some stained water than they do in clear water and vice versa.

Really Dark Water

At times we have to fish in water that is extremely dark, where light is almost non-existent. This could be water that is very deep, or it could be water that is so stained that light is just not penetrating very far. You might also be fishing at night. In these cases, the color under the water can be so dim, that the very low signals from the cone cells in the eyeball are being overridden by a different set of cells known as rods.

Unlike cones, rod cells only distinguish between shades of black and white. Effectively, they signal contrast, or differences between shades. Furthermore, light entering from the periphery, your peripheral vision, tends to be seen better by these rod cells than light coming from directly in front of you. If you don’t believe it, just step outside on a dark, starry night. You will notice that there are some stars that are easier to see when you don’t look directly at them. This is precisely due to the fact that more of that light is being “seen” by the rod cells in your eyes vs the cone cells.

When it comes to lure selection in these cases, think contrast. Black and whites with sharp contrasts are great choices in these conditions as they will stand out to a fish when not much else will. A lure that rotates or vibrates with the right combination of black and white (or glow in the dark) will effectively look like a strobe light under the water to a fish in these dark conditions.

Good luck out there! If you enjoyed this article, please let us know by dropping a comment below and consider subscribing to our blog.

5 Tips to Help You Become a Better Fisherman

* This page contains affiliate links. The Great Lakes Fisherman may earn a commission on items purchased through these links. For more on this, please click here.

With many of the skills we develop in our lives, the process involves learning the right technique and then practicing it thousands of times. But fishing is a unique activity. It involves countless techniques. Some of them work great some of the time, but poorly at other times. So becoming a better fisherman has as much to do with versatility as being great at any one method. With that in mind, here are 5 tips that will help you become a better fisherman.

5. Watch YouTube Videos

The old ways of learning about fishing techniques usually involved watching the few outdoors shows that were offered by your local tv or cable provider, reading magazine articles and occasionally renting a video. That expertise was limited to a few big pro-fishing names that were fortunate enough to land their own TV show or write features in the few outdoor magazines of the time. But the information was usually pretty high-level and not very specific.

But with YouTube, we can learn from many more people, both amateurs as well as professionals. Many of these folks are better in-tune with the specific bodies of water and the species we are targeting. And there are some amateur fishermen out there that can hang with the very best of professionals when it comes to their fishing skills. YouTube has volumes of great videos ranging in duration from a few minutes each to entire feature length programs. This is an easy and very convenient way to learn.

4. Socialize with Other Fishermen

Fisherman are generally good people. While they are not likely to divulge the location of their honey hole (nor should you expect them to), many of them are more than willing to give you a few pointers on techniques to help you put more fish in the boat.

If you have the time, joining a fishing club can be a great way to meet and socialize with fisherman that are interested in the type of fishing you enjoy. You might also make some new friends along the way.

If fishing clubs aren’t your thing and you’re looking for an easier way to socialize, a fishing forum is a great way to trade information with fellow fishermen. Being in Michigan, I often used the Michigan Sportsman Forum, but there are similar forums in most states. Our Regs & Reports menu includes links to several such forums related to fishing the Great Lakes region.

3. Think Like a Fish

Fish are relatively simple in terms of what drives them. For 80-90% of the year, they are driven by the need for food. The other 10%-20% they are either preoccupied by spawning, prepping to spawn or recovering from spawning. Thinking like a fish means knowing which of these modes the fish are in, and within the body of water you are fishing, which area will provide them with their needs at that time. Each and every time you head out on the water, you should ask yourself, what is driving the fish and where would they likely be to obtain their goal.

2. Experiment

As fishermen, we sometimes get caught in the trap of continuing to try the same method that has worked in the past, regardless of the results we are getting. It is appealing because after all, the method has a proven track record. But over time, a fish’s environment changes and they must adapt accordingly. Sometimes, their behavior can change several times within a day or even a few hours. This means that you must adapt if you expect to catch fish.

Once you have located fish, it shouldn’t take long to catch them if the right presentation is used. If you aren’t achieving results in 10-15 minutes, you need to try something else. Try changing baits, colors and even techniques. By finding what they are concentrating on, your catch rate will increase dramatically.

1. Put in Your Time

When it comes to fishing, there is no “one size fits all”. This is because each lake, river or stream is unique. Where walleye hang out on one lake may not be the same on another. As the old saying goes, “90% of the fish are in 10% of the lake”. But it will take a little time to figure out where that 10% is on each body of water.

So while the tips above will better prepare you for your fishing trip, trial and error will train you the best. There is no substitute for this. Like it or not, following the above tips will not pay off if you don’t spend time on the water. But as you spend the time, and better understand your target, your catch rates will continue to get better and better.

There will still be days, of course, where you find yourself skunked, but they will become very few and far between. But spending time on the water and utilizing the tips above will help you become a better fisherman!

Three Knots Every Fisherman Should Know

* This page contains affiliate links. The Great Lakes Fisherman may earn a commission on items purchased through these links. For more on this, please click here.

When it comes to fishing knot selection, some are better than others. There are countless knots out there and each have their advantages and disadvantages. For fisherman, knots can be difficult depending on the conditions. Tying a rope is one thing. But trying to tie a 4 lb flourocarbon leader onto a hook with a eyelet the size of a pinhole is another matter completely. Furthermore, doing so while bouncing around in a boat can make the task nearly impossible. While there are plenty of specialty knots to know for specific situations, here are the top three knots that every Great Lakes fisherman should know.

The Palomar Knot

Best Use: Terminating line at hook/lure

Dexterity Level: Easy

Strength Level: Strong

Advantages: Terminating line at terminal tackle

Disadvantages: Threading through small lure eyelets; only practical for terminal tackle.

The Palomar knot is, in my opinion, the best fishing knot for tying on terminal tackle. It’s balance of strength and its ease of use make it the ultimate knot for tying on your lures. One of its major drawback is that can only be used for tying onto your terminal tackle. This is because one of the steps in tying the knot involves passing the lure through a loop in the line. While this is great for hooks, swivels and smaller lures, it can get very cumbersome for tying on a 4 foot long leader, for instance. It is also very difficult to tie onto very small lures and hooks as the line needs to double up though the eyelet. Nonetheless, as fisherman, the final knot that attaches to our larger hooks and swivels are some of the most common knots we tie, which is why this is a favorite of many.

The Improved Clinch Knot

Best Use: Terminating lines at small terminal tackle; attaching leader to a swivel that is already on the main line

Dexterity Level: Easy

Strength Level: Medium

Advantages: Terminating line anywhere; good for smaller tackle

Disadvantages: Not as strong as the palomar; not the best for terminating medium-large tackle.

The improved clinch knot is often the first fishing knot we learn. Its versatility makes it great for use in many situations. It is particularly good for tying smaller line to smaller tackle as the line only passes through the eyelet once. It is also a great knot for adding a new leader into a main with a barrel swivel already on the line.

The Double-Uni Knot

Best Use: Tying 2 lines together

Dexterity Level: Medium

Strength Level: Strong

Advantages: Relatively easy to tie; strength

Disadvantages: There are arguably some stronger line-to-line knots out there

Every fisherman needs to have one knot in their arsenal for line-to-line terminations. In my opinion, this is the best all around knot for this purpose. While no line-to-line knots are easy to tie, especially in a boat, this one is one of the easiest. It is also a very strong knot and should hold up in the toughest situations.

Non-Native Species in the Great Lakes

* This page contains affiliate links. The Great Lakes Fisherman may earn a commission on items purchased through these links. For more on this, please click here.

The Great Lakes contains dozens of non-native species of fish. Some of these fish were introduced accidentally and some, by design. While you probably know about some of these, such as the sea lamprey or the round goby, you may be surprised by some of these fish that you thought have always been here. Here, we will examine some common species you didn’t know weren’t native to the Great Lakes.

Alewives

Alewives are a forage species of fish from the ocean. Like many non-native species, they are believed to have arrived in the Great Lakes via the dumping of ship ballast water in the 1860s. Once they were here, they competed for food with native species. To help control their populations, salmon were introduced.

Salmon

There are 4 species of Pacific salmon (chinook, coho, pink & kokanee ) that have been stocked in the great lakes since the 1870’s. Although there were previous attempts to introduce salmon to the lakes, it wasn’t until the 1960’s, when alewife populations had exploded, that the salmon populations established themselves. While 3 of these species persist to this day, the kokanee (sockeye) salmon was not able to sustain itself and is believed to have died out shortly following its introduction.

In addition to the 4 Pacific species of salmon, there is one additional species of salmon, the Atlantic salmon, that is found in the Lakes. However, this species has a slightly different story. The Atlantic salmon was native to Lake Ontario until the late 1800’s when overfishing, pollution and the destruction of spawning habitat is believed to have resulted in the demise of the population. Similar to the introduction of the Pacific salmons, the Atlantic salmon, having failed introduction several times prior, finally became established in the 1970’s due to the high alewife populations.

Common Carp

Common Carp are believed to have been brought to the region in the 1800s because of their popularity as a food source in Europe. According to the Michigan DNR, the carp are not considered by authorities to be “invasive” as they don’t cause harm to the state’s economy or the environment. The common carp is a species of the minnow family.

Buffalo

Although they look similar to the carp, buffalo come from a completely different family. These fish are the largest members of the sucker family. There are 3 species of buffalo (out of 5) that are in the Great Lakes and all are non-native. Two of them, the smallmouth buffalo and the bigmouth buffalo, are believed to have been introduced in the 1960’s while the black buffalo is believed to have been introduced in the 1980’s. The process of their introduction is not yet understood.

Flathead Catfish

Though the source of their introduction is still being investigated, flathead catfish are known to have been in the Lakes since the 1920’s when populations were discovered in the Kalamazoo and Grand Rivers, tributaries of Lake Michigan. The range of these fish is reportedly still expanding into the northern reaches of Lakes Michigan and Huron. To date, their impacts to other species appears to be minimal to non-existent.

Round Goby

The round goby is one of the more recent species to have been introduced to the Great Lakes, having only established themselves here in the last 30 years. The round goby is another species that arrived through ship ballast water dumping. While the goby has its downsides, it has provided a benefit to the world-class smallmouth fishery that the Great Lakes offer. For more on the relationship between the round goby and smallmouth bass, check out this article.

Rainbow Smelt

Although smelt are a popular gamefish and table fare, many people don’t realize that these fish are not native to the Great Lakes. Rainbow smelt were planted in Crystal Lake in northwest Michigan in 1912. The fish made their way to Lake Michigan via the Betsie River and quickly established themselves in all of the Great Lakes.

Populations of these species have declined sharply in recent decades and researchers aren’t entirely sure why. It is largely believed that the introduction of quagga and zebra mussels into the food chain is a contributor, but the exact mechanisms of their impact are unknown.

Grass Carp

The grass carp is 1 of 4 species of invasive (Asian) carp that are posing one of the most significant threats to the Great Lakes in modern history. To date, the grass carp is the only species to have been found in the Great Lakes and measures are being taken to reduce, and hopefully eliminate, its impact. For more on the latest efforts to prevent and control impacts by Asian carp, check out this article.

Sea Lamprey

One of the more problematic species to enter the fold is the sea lamprey. Previously

stopped by Niagara falls, the Welland and Erie canals allowed these blood-sucking parasites to enter the remaining Great Lakes upon their completion. These fish have had devastating impacts on other Great Lakes species and have required millions of dollars in annual funding to control their populations.

White Perch

The white perch is another species that took advantage of man-made canals to progress into waters further inland. Being native to the North Atlantic region of North America, these fish can now be found throughout the Great Lakes thanks to the construction of the Erie and Welland canals which allowed their passage deeper into the lake system.

Brown Trout

Brown trout were introduced to the region via stocking programs. Not only are brown trout not native to the Great Lakes, they are not even native to the United States. Brown trout were brought to the U.S. from Germany in the mid-1800’s. Like salmon, early attempts to stock brown trout in Lake Michigan were unsuccessful and it wasn’t until the

1960’s that the fish took hold as a result of newly refreshed stocking programs.

Rainbow Trout & Steelhead

Rainbow trout and steelhead were also introduced to the Lakes via a stocking program in the late 1800s. These fish had more success than did the programs for brown trout. Rainbow trout are inland fish that live and spawn in the same range. The anadromous (lake/ocean migrating) form of the fish known as the steelhead, live much of their lives swimming in the open lakes but migrate to their native streams and creeks for spawning. Steelhead are now one of the most popular fish to pursue in the region, offering folks in the eastern half of the country a taste of what the west coast has had all along.

Redear Sunfish

Relatives of the bluegill known as redear sunfish were believed to have been introduced to the region around 1928 when they were stocked in some Indiana waters. These fish are known as “shellcrackers” in their native region of the southeast, due to their ability to crack mollusk shells. They have proven

to be a popular gamefish both in the summer and through the ice and tend to inhabit similar waters as their other sunfish cousins.